Introduction

CREATIVITY LIE #1: The Genetics Lie

Creativity is Inborn. Aka: I’m Just Not That Creative

You are not just naturally more or less creative than him, or her, or anyone else. There is little convincing evidence of a creativity gene, or even of a collection of genes that add up to creativity. Many studies have been done that have failed to show any birth advantage at all. This includes studies of fraternal and identical twins designed to clearly measure the impact of nature and nurture, that found zero impact of genetics on the results.

Sure, some people are more creative than others. Some people are perpetual innovators, and others live life the same way for years on end. It’s hard to argue that, say, Edison, was not more creative than most others living in New Jersey at the time. But all data points to the understanding that Edison’s 1000 plus patents were not his birthright. He famously said that his genius was “1% inspiration and 99% perspiration,” and science, so far, has proven him right.

In the age-old nature vs nurture argument, creativity comes down hard on the nurture side. Genetics seem to have only one clear impact on creativity: we are all born with it. Watching small children do creative tasks, it’s hard to pick out one who shines above the others. One three-year-old may be more intelligent, more perseverant, or more focused than another – but not more creative.

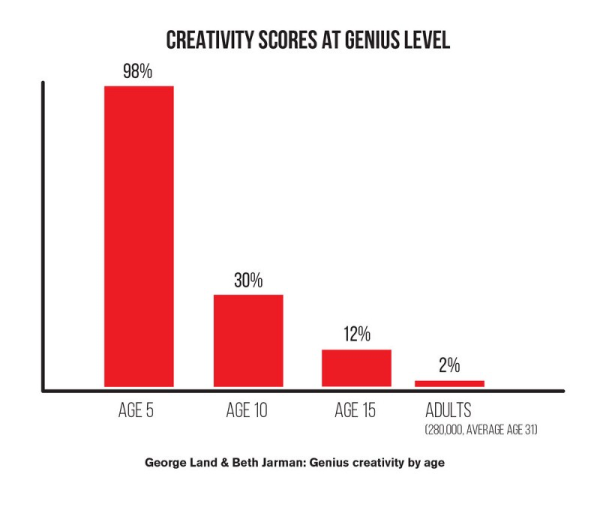

Over time, though, intelligence, perseverance, and focus all play into a learning of greater creative skill, or perhaps it is better classified as a more resolute refusal to unlearn it. Because another thing that evidence seems to clearly show is that creativity is not gained as we grow up, but lost. Picasso said that all children are artists, with the trick being to remain an artist once we grow up. A seminal study by George Land showed this with frightening clarity in 1968, the year of my birth.

Tracking the same children as they got older he found their scores on creativity testing radically declined, and shockingly fast. While the initial test on 5 year olds ranked 98% of them creative at “genius level”, by the time they turned 10, only 30% of them reached this ranking. Five years later, at age 15, the total plummeted to 12%. And by the time they were adults, only 2% could be considered “creative geniuses”. Nothing changed about their genetics. All that changed was, they grew up.

Land’s interpretation of this was that modern education forces us to simultaneously run our convergent and divergent thinking patterns, that is, the imaginative and critical faculties. This way of operating crushes our creativity so badly that we end up with the results above, outcomes so shocking and depressing that they formed the basis for Land’s Ted talk in 2016 – nearly 50 years after the study. The key to solving that, of course, is to separate these two ways of approaching things, just as children do. But that’s the subject for another article.

This was not some fly-by-night study. Land used the same creativity test he had created for NASA to help them select innovative engineers and scientists.

Well ok, not quite. Roger Beaty, a Postdoctoral Fellow in Cognitive Neuroscience at Harvard, completed a study just last year that showed convincingly that highly creative people have a different brain structure than less creative people. Creative people’s brains, it seems, have a dense and intricate neural network spanning three specific brain systems: the default, salience and executive networks.

The default network is active when people are engaged in spontaneous thinking, such as brainstorming, daydreaming or imagining. The executive control network is used for focus, such as evaluating if ideas will work. The salience network is a switching mechanism between these two. For in most people, the default and executive networks do not work at the same time. Beaty’s study showed that creative people are better able to run the systems simultaneously. In other words, it has something to do with the strength of the salience network. And in fact, highly creative people CAN maintain an ongoing balance between inventing and judging, the paradox that stops most people in their tracks. So Beaty’s research does reinforce the notion that some adults are more creative than others. Creative minds are wired differently than “uncreative” ones.

What Beaty’s research doesn’t do is provide any evidence at all of genetics at play. Nothing in his research made the claim that creative superiority was inborn. To do so they would have to study the actual growth of the neural networks from early childhood.

There is, however, some more convincing evidence of genetics playing a part in creativity. Momentarily convincing that is.

Read Part 2 for more on this.